-

-

Formally, The Mountain consistently toys with the existence of an elsewhere, some undefined (presumably demon-free) space framed by the oft-repeated openings in the landscape—square apertures in the sun-bathed, crenelated ruins where Zein romps as a child, the endless sea horizon, day-lit gardens in which animals graze. These are equally consistently contrasted with a series of closures—gloomy slivers of doorframes through which wary villagers peer, constricted alleyways, and a warren of candlelit claustrophobia-inducing cells. And beamed through at least one channel for nearly the duration of the film, it is there: the mountain.

Whatever path you take through Moataz Nasr’s practice, no matter if you cluster his categorisation-defying works by medium, if you slice them by political intent, if you dice them up into periods or if you bundle them by thematic thrust, you will be confronted, at multiple points in your journey, with a recurring ingredient: the artist’s feelings.

Subjectivity rears its head nearly at every turn in Nasr’ two-decade career. An Ear of Mud, Another of Dough (2001) crystallises his indignation at societal complacency. Father and Son (2004) is an intimate and deeply uncomfortable coming-to-terms with a long-denigrated parent. Cairo Walk (2006) offers a highly personal cartography of the chaotic crannies of the Egyptian capital. Made entirely of matches, Arabesque (Lost Heritage) (2013-14) flings twin slaps at the geopolitics that led to the invasion of Iraq and generalised indifference to a vanishing ornamental heritage. The five-channel film The Mountain (2017), first written when the artist was eighteen, was made for his three daughters, in celebration of their independent spirits[1].

Obviously, subjectivity is every artist’s raw material, and emotions are equally constant sparks igniting a process of exploration, deconstruction and creation. Yet Nasr’s practice seems to be cleft into two distinct emotional segments: one fuelled by a register hinged to his own personal anger; and another that leverages introspection in pursuit of a more profound kind of witnessing. The former produced works that rile the viewer, indulge in indignant finger pointing, or lob political grenades; the latter cultivates complicity. A strictly time-bound fault line is hard to place with any certainty, and indeed the two impulses may intermingle, ebbing and flowing throughout the practice: Father and Son’s three-hour-long clash of sensitivities, from 2004, is ultimately a gesture of reconciliation, whereas 2019’s Petro Beads is a damning conflation of the petroleum industry and religious extremism. The angry young man and the sensitive observer seem to coexist. As critic/curator Sami Njami wrote in a 2005 catalogue accompanying Nasr’s solo show at Jordan’s Darat al-Funun, “his humanity dictates his choices.”

What this cosy emotional humanist lens tends to obfuscate, though, is Nasr’s skill as a strategist. While most writing about Nasr examines the upstream—his personal catalysts—we mistakenly disregard how keenly he is invested in strategizing how the work is viewed. So, far from dwelling on the artist’s rich subjectivity and benevolent humanity, I would argue that an entirely contrary approach—namely, exploring his foregrounding of viewer reception—would offer an alternative inroad into a heavily travelled practice. I propose, therefore, to look at Nasr’s practice not from the artist out, but rather from the public back.

The Mountain is a site of latency, a strategy Nasr has employed deftly in precedent works. I refer to latency not as content—a narrative component of the work—as one sees in the practice of Lebanese duo Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige, like Latent Images, the third part of the Wonder Beirut project (1997-2006), depicting images of drawers containing undeveloped rolls of film. Nor do I mean elements in a work that are simply invisible, remain “non-activated,” or are potentially entirely fictive, as exhibited in many of Ryan Gander’s Alchemy Boxes. Rather, Nasr imbues his work with strategic latency: it is built on the notion of its own potentiality, and the viewer is wound up in this promise.

Two precedents in Nasr’s practice provide examples.

Tabla II (G8) (2006) is an updated installation version of the 2003 video work The Tabla. The original video closes in on a master tabla player caressing his drum before lightly tapping and then playing, thus activating and transforming the otherwise inert object. Latency here is largely inherent in the object itself: the transformative act, lodged in this video whose wider message concerns the production of art, or perhaps even the generation of meaning, hardly makes this deployment of latency strategic. However, in the G8 update—the reference to the then-active Group of Eight power summit endowing the work with a political sting—an assembly of dozens of different sized tablas, distributed in a semi-circle around the projection, functions as a kind of audience, like some mute spectatorship. The video image, enlarged in this version, seems to cast a mesmerising spell over the motley congress of stout, silent instruments. Held temporarily in the glow of the projected performing drum, the “witness” drums overlap with the actual human audience, not as a kind of stand-in, but as elements in a strategic gesture confronting us with our own potentiality.

This is not mere analogy. The artist is not saying we are “like” the docile soundless instruments. By plunging us into the vortex of power dynamics swirling in the work, he makes us them. The moment we step into the exhibition space, we are the complacent onlookers of a warped global distribution of power. We become the muzzled mass, the voiceless bystanders of history, erect, empty vessels. And yet we are also the holders of a potent capacity to activate our own cacophony, to explode into sound, to revolt. Beyond the rather obvious latency of the drums, the latency of this implicit, insidious rallying cry delicately yet deftly emerges from the work. Ultimately, Nasr has woven the viewer into his wider worldview through the fibres of her own latent potential.

The two-channel video Father and Son (2004) began as a dialogue between Nasr and his father after the death of the artist’s mother. For all its stark simplicity—talking heads shot with two static cameras in a salon—it an unusually uncomfortable viewing experience. Deeply angry with his father at the time, particularly for what Nasr saw as his mistreatment of the artist’s mother, he provoked this conversation to resolve his feelings. The tension in the film springs less from a simmering filial animosity, than from the immaterial presence (and potential vindication) of the deceased matriarch. The mother is absent, yet she is everywhere. She inhabits the walls of “her” salon, punctuates the breaths and silences of the father-son pair, a spectral presence observing as the answers to her unasked questions are committed to film—why did you make me a housewife, why were my talents left to wither, why did you give me no affection? She is a latent character. And, once again, the artist makes us become her.

In the work, Nasr is our porte-lecteur, the narrative function that, literally, carries a reader (or viewer) through a text (or discourse) by means of a heightened identification. Yet in Father and Son, while Nasr is certainly his mother’s advocate, trying to wring some sense of justice from a staunch, quasi-tyrannical patriarch, he is not fully “channelling” her, intent on settling scores of his own. Our identification shifts away from him and towards the mother herself. We root less for the pair’s eventual reconciliation, and more for some kind of reinstatement of a disparaged woman’s dignity. The overlap with the viewer occurs insidiously, hinged to an intensifying distancing from the father as he argues his case. His throaty soft-spoken words nonetheless strike like slaps: “She must obey me,” “Submission,” “I didn’t want to get married. I did it for my mother.” The work never wallows in the confessional, nor does it collapse into a filmed ego exercise of self-discovery-through-confronting-my-parents. On the contrary, Nasr has “rigged’ the work to incite viewer identification with an entirely latent presence, steering the work clear of the cliché traps into which it could have easily fallen. By hoisting the viewer to the level of the mother, by soldering us to this potent absence, Nasr redeems not only the work, but also his mother’s memory.

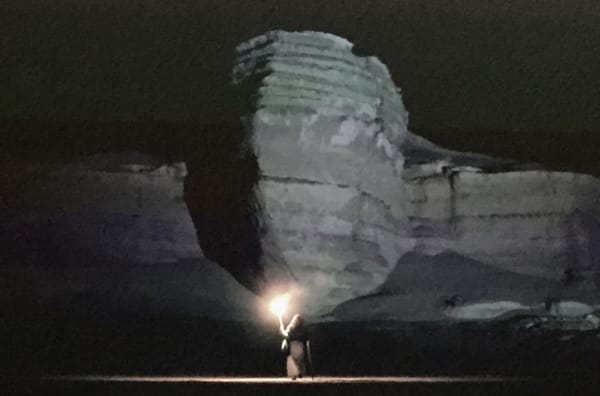

The twelve-minute, five-channel video The Mountain (2017) is built on a classic narrative structure: an omniscient narrator introduces us to the inhabitants of a rural Upper Egyptian village in the throes of long-term fear fuelled by a mountain-dwelling demon who speeds the demise of those foolhardy enough to venture out at night. Zein, a child when we first see her, returns to the doomed village as an adult after completing university in Cairo. She defies the supposed demon by planting the sheikh’s staff in the mountaintop one pre-dawn night, as a torch-bearing band of villagers gapes below. The plot remains unresolved: Zein shrieks and collapses; the assembly rather clumsily questions whether or not she died.

Beyond the non-resolution, a Nasr hallmark (although generally delivered in less strict narrative configurations), latency crops up in recalls of previous works. The ears that suddenly dot the walls of village houses, suggesting surveillance and constraint (by the demon? the state? are they the same?) are reminiscent of the early An Ear of Mud, Another of Dough (2001) which lashes out against complacency. As Zein prepares her bold demon-bashing outing at night, other screens in the five-channel installation serve images of a matchstick sculpture spelling out “Ana hurra” (I am free), which, set aflame, consumes itself. Harking back to the Lost Heritage matchstick works—the latency of dormant destructive powers, and the resulting wildfire of defiance—the images also conjure the interactive sculpture I Am Free (2012).Formally, The Mountain consistently toys with the existence of an elsewhere, some undefined (presumably demon-free) space framed by the oft-repeated openings in the landscape—square apertures in the sun-bathed, crenelated ruins where Zein romps as a child, the endless sea horizon, day-lit gardens in which animals graze. These are equally consistently contrasted with a series of closures—gloomy slivers of doorframes through which wary villagers peer, constricted alleyways, and a warren of candlelit claustrophobia-inducing cells. And beamed through at least one channel for nearly the duration of the film, it is there: the mountain.

Cast as the mute and immutable villain of the story, the mountain is the inert epicentre of fear, the craggy counterpoint to the fluid and virtual elsewhere that seems moored to childhood. Both are at once present and absent, as much cloaked in imagination as reality: the breezy expanses of memory and the present Mount Scary exist only because we are complacent enough (or so conditioned by a short-sighted patriarchy) to endow them with power. The recurring Nasrian message—namely that power in the face of a cowardly public will only continue to thrive and thwart individual agency, unless that public activates itself—seems valid here as well. If “fear is our greatest demon,” as the artist frequently explains when discussing The Mountain, complacency is its henchman. The acts of defiance in the work—Zein’s mother overriding her husband and sending Zein to school; the uncovered, brightly attired Zein yanking the staff from the sheikh; her will to rupture the demon myth—signpost possible, although murky, alternatives.

However, the strategy of latency afoot in Father and Son and Tabla II (G8)—heightened viewer identification with a virtual character, the covert call to activism—works differently here. The narrative structure precludes any real overlap of identification, so no slippage of the viewer onto the character, whether present or absent, occurs. Whereas the viewer was folded into the experiential web of the work in the other two pieces, there is a distance established by the crafting and delivery of so straightforward a storyline (omniscient narrator, beginning-middle-end structure, and so on). The Mountain, then, becomes a kind of parable, a fable of sorts. As such, it would normally valorise defiance, elevating Zein as a role model, framed as an exemplar of vanquishing fear and exposing unjust power structures. Yet nothing of the sort: the role model completes no feat (other than driving the sheepish night-dreading villagers from their domestic recesses where fear coats the walls) and the over-insistence on the uncertainly of her fate (a kyrielle of “Is she dead?” “Is she alive?” closes the work) extinguishes the very point of the fable’s lesson. Nasr takes us to the brink and stops, suggesting that the cycle is endless: the stubbornness of fear-induced complacency defies defiance.

“The only thing that frightens me are humans,” utters Zein as she returns to the village post-studies. Nasr’s works confront us with power structures and social dynamics that are stronger than ourselves. Yet the real enemy is somehow within. Solitary acts of defiance seem insufficient; without collective change, we are tethered to an eternal trap. While it may be accurate, as stated earlier, that Nasr’s humanism guides his choices, he is also highly critical of societal inaction, sometimes to the point of indignation. But here’s a fair (and open-ended) question: are these strategies that so skilfully prioritise viewer complicity acts of humanistic compassion, or the ultimate critique implying that we are already lost?

-

-

-

-

Pascal had his abyss that moved along with him.

- Alas! all is abysmal, - action, desire, dream, Word! and over my hair which

stands on endI feel the wind of Fear pass frequently.

Above, below, on every side, the depth, the strand, The silence, space, hideous

and fascinating...On the background of my nights God with clever hands Sketches an unending nightmare of many forms. I'm afraid of sleep as one is of a great hole.

Full of obscure horrors, leading one knows not where; I see only infinite through

every window,And my spirit, haunted by vertigo, is jealous

Of the insensibility of nothingness.

- Ah! Never to go out from Numbers and Beings!

This latest work by Moataz Nasr is a parable in the form of a cinematic film. Much like traditional Oriental tales such as One Thousand and One Nights, the artist uses the seemingly simple surface of a story to touch upon moral, philosophical and ethical concerns. Like solving an enigma, the viewer must actively participate in order to unravel the subtleties that are present within the work.

The Mountain is in itself a place charged with symbolic value which has fascinated our terrestrial imagination throughout the ages. It was on the summit of Mount Sinai that Moses received the Ten Commandments. It was on the summit of Mount Olympus that the ancient Greeks established palaces for their gods. The Mountain is first of all a mass that dominates us, and through its shape it is the keeper of unknown secrets. It is another world within our world; and the mountain is untamable. The gods and demons that haunt its topology laugh at our attempts to attack it because, as in every endeavor, it is not the result of an action that matters most, but how the plan is conceived and, as in every journey, one must be prepared and one must have a clear goal in mind, along with the means to approach it.

There. And so it stands: The Mountain. As if the landscape itself was built upon its element. It is appeasing evidence around which villagers go about in their daily life; under the blue light of a relentless sun. Everything stands still just like the calm before a storm is about to hit. And then, both soothing and worrying, the cold night gently settles in and the light spreads across the visible spectrum orchestrating a trans-lucid halo that covers everything with a bluish shining quilt; the stars sparkle in the sky and in the distance a dog barks, a child cries. All is silent...

Multiple doors slam shut, and keys shake and jingle against keyholes and their locks; there is not a shadow in sight, not even of a passer-by being delayed by the ongoing work in the fields. And then, it crept. Like a heavy and thick oil that is suddenly and instantly observed. Fear. Its smell as familiar as it is elusive. Fear. Fear is a blackhole haunted by ghosts, a hypnotic and throbbing hammer that takes away all willpower and prevents us from hearing and thinking- it blinds. Fear evolves at night in the

attics and in the caves within the darkest and most fetid of corners; within the forests, where the trees agitate their leafy and threatening arms. Fear is like a vicious snake that wanders in blackness, and suddenly, emerging out of nowhere it stabs its victim.

Fear is a rat that lurks in the sewers of our conscience. And yet the night is always beautiful.In Nasr's oeuvre, the mountain is not a place of wisdom but rather the home of a demon - a metaphorical monster growing from beneath the earth within us, from our uncertainties, frights and cowardliness. The unknown monster that no one has ever encountered grows stronger from generation to generation until its power becomes total and absolute. His power is in fact the making of our own creation. We are the only ones who can be held responsible for its degeneration. We give it

a space at the center of our lives and passively accept a false reality. Because of our conformism and blind trust of lost traditions, our society is umbilically dependent upon this sickness. Nobody would dare defy the status quo and question the myth that had been founded strictly according to the rules, and yet it would just require 'a little bit of nothing' for us to disrupt and question the past certainties that we once believed were unchangeable. We can cause these foundations to tremble at their base. Just 'a little bit of nothingness' can carry us out of limbo and away from the shores of our ignorance. This 'nothingness' can be our refusal to capitulate in the face of fatality and the certainty that we, as human beings, hold the ultimate powerto shape our destinies.

This 'nothing', this 'little more than nothingness' can be found at the opposite end of ignorance and obscurity. One must be wary of the obscurantists for they fear light and they do not appreciate science or art, or, in fact anything that could question their parameters. Perhaps it is this very fear and ignorance that will one day lead those who bow down to them to open their eyes to their actual nakedness and make the necessary changes.

Zein, the protagonist in our fable, embodies freedom. The same kind of freedom that philosophers call free will. It will enable her to separate herself from her 'self' and rediscover the world through a new perspective. Zein is a young woman who leaves the mountain village as a child in order to pursue her studies in the capital, it is during this period that she starts to challenge her own certainties. One day, on her way back to the village she encounters a lady on the road and as soon as she tells the lady where she is from the woman asks her, almost mechanically, if she is not afraid. Zein bluntly snaps back, "I am only afraid of human beings".

This phrase informs us of her conviction that the only fears that matter are those that have a source and a possibility to be overcome and dominated. Fear weakens, it renders one inert and it gives destiny the chance to be handed over at the mercy

of versatile fatality.Without us even noticing, fear can swell up from within whilst it disfigures our most intimate thoughts. In Stefan Zweigl's 1928 novel Fear, the author describes the same type of fear that we see in The Mountain. A fear that has sucked the life out of everyone in Zein's childhood village; "Fear is worse then corporal punishment because it is always determined and preferable to the tortuous and undetermined waiting that stretches out infinitely. Relief from it only comes when its punishment is received. And don't be fooled by its tears for it is only now that they show. They were there before building up on the inside; and inside is where they are the most destructive". This is the very enemy against which Zein will deliver battle upon her return. Fear has destroyed everything within the villager's psyche, including their very desire for emancipation. Her purpose is to shatter the unbearable waiting that would otherwise lead to catastrophe. She is young and frustrated, and she rejects the so-called fatality that has long disabled the villagers. By setting herself the task of climbing the peak of this intimidating mountain, Zein chooses to defy her own demons.

The artist symbolically uses the character of Zein to warn us that fear is the enemy, our enemy; and it is not a weak or average one but an overpowering, and destructive nemesis that should never be underestimated. "Fear of the enemy will even destroy

its resentment". (Fyodor Dostoevsky; Demons 1871). Zein's departure from her hometown to pursue her studies is the catalyst to a

chain of successive events that will provoke turmoil within the daily rural monotony. It is not by chance that Nasr chose a woman as the primary character; her decision to leave the village goes against the patriarchal mindset of her environment, one which restricts the role of a woman to a fragile individual in need of protection.

Nasr confronts this image. Rather than celebrating physical strength he praises Zein's moral virtues that have the power to proverbially move mountains. Zein chooses to execute her mission at night as it is the only moment that the demon leaves the mountain. Through her battle she pushes the doors open and allow the villagers to awaken from their never ending night so that a ray of light may finally reach them."No passion nor fear is safe without the need for it to be transcended. Fear has the particularity to perpetually exaggerate the subject and to weaken our feeble imagination. Each day brings forth a new challenge; today certain ideas seem dangerous but tomorrow the danger could be impersonated by a man or a class. We are increasingly shutting each other out with barricades by locking our doors and our minds until there remains no day, not even the slit of a gap through which a thin line of light can leak". (Jules Michelet; The History of the French Revolution, 1850).

When the young woman decides to go against everyone's advice (including her expedition companions) they all begin to cry as if she is already lost. Yet, right there and then she had already accomplished a miracle. Her boldness has paved the way for the once subdued feelings of anger and rebellion. Now they can come back to life, the men will begin to feel ashamed of allowing a woman to fight danger, single-handedly, whilst the women will feel pride at being represented. Together, they will provoke a movement, a wave that will spread across every one of the villagers, bringing them together to form a parade that echoes behind Zein's footsteps.

Thanks to the actions of one, the whole village has regained the will to fully live again. The villager's backs have straightened out, their hearts beat against their chests more vigorously than ever before; even the blood that circulated slowly begins to speed up. Life reclaims its rights. Each woman and each man is poised

to renew him or herself, to be reborn."He had the intimate conviction that human beings do not experience birth simply during the moment when they come out of their mother's belly but instead life will obligate each woman and each man to give birth to one's self over and over again".

(Gabriele Garcia Marquez; Love in the Time of Cholera, 1985).

No happiness or misfortune should ever be taken for granted. Nothing, not even the most powerful determination can contain us within an immutable humanity. We can only decide what we will become tomorrow if we consistently choose the path that questions the values that we have accepted as eternal. We must choose the path that inspires us to shake off the dust from our own comfort zones.

Nasr suggests that our future can only be carved into the marble of our minds and that more often than not, we are the main source and cause of our own fears. The village, freed by Zein's courage, could be any home, village, country or continent. It exists and it doesn't exist. It is only a stage inhabited by human figures that are moved around by the instructions of the artist. They are interchangeable, replaceable; and all that will remain is this universal story and its teachings.

Let us now take a step back, we shouldn't be too preoccupied with this lost village somewhere between the Middle-East and Africa. Let us now expand our view to a global level, from North to South, East to West. Let's hover above the continents and open our eyes. What do we see in this stammering and young twenty first century, in this retarded third millennium? And what do we hear? Could it be anything other than the deafening thunder of fear? Fear of the other, fear of one's own shadow. Fear of the past and fear for the future. Fear of one's self?

Can we find the same courage as Zein to go against the metaphorical mountain, to confront our demons with our own bare hands? Or are we doomed to remain passive? Will we wait for fear to close in on us and push us off the edge, down into the abyss of our own despair? An abyss that will become the graveyard for our humanity, a ditch that could very well be the inverse double of the mountain.

Pascal had his abyss that moved along with him.

- Alas! all is abysmal, - action, desire, dream, Word! and over my hair which

stands on endI feel the wind of Fear pass frequently.

Above, below, on every side, the depth, the strand, The silence, space, hideous

and fascinating...On the background of my nights God with clever hands Sketches an unending nightmare of many forms. I'm afraid of sleep as one is of a great hole.

Full of obscure horrors, leading one knows not where; I see only infinite through

every window,And my spirit, haunted by vertigo, is jealous

Of the insensibility of nothingness.

- Ah! Never to go out from Numbers and Beings!

-Charles Baudelaire; Le Gouffre (The Abyss), translated by William Aggeler

(Fresno, CA: Academy Library Guild, 1954) -

-

-

Musical Manifest: The Trailer

The Mountain : Moataz Nasr

Past viewing_room